Jun 08, 2023 by Mark Dingley

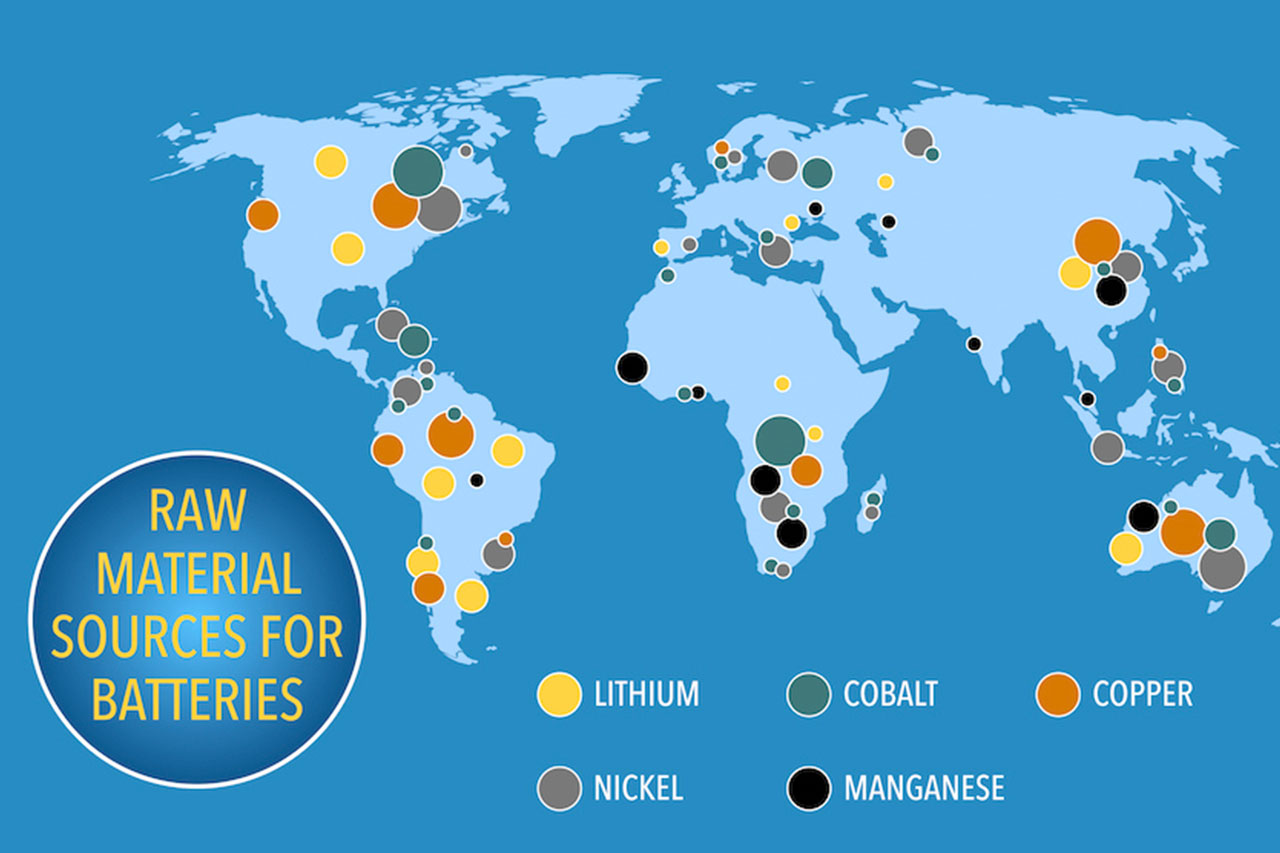

Demand for critical minerals is set to rise two to fourfold by 2030, as countries seek the elements needed to manufacture batteries, electric vehicles and solar panels.

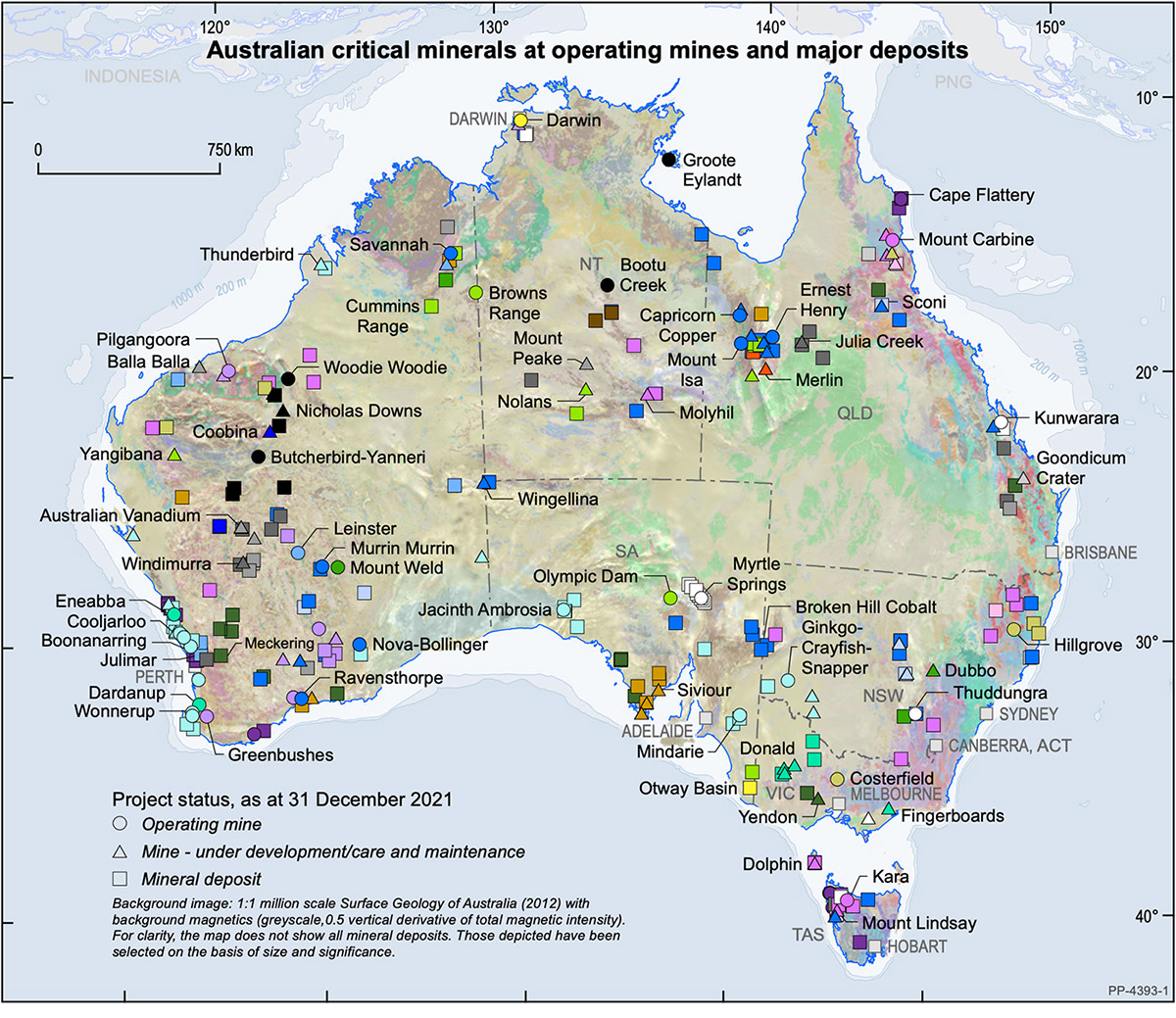

This is good news for Australia, which has some of the world’s largest reserves of critical minerals.

You could say we are “The Lucky Country.”

According to Geoscience Australia’s World Rankings 2021:

But is Australia just “a giant quarry”, as Curtin University’s Professor of Sustainability, Peter Newman, told the ABC?

Australia is a world-leading exporter of high-quality, ethically sourced minerals extracted using environmentally sustainable practices, according to the government’s Global Australia website.

But what if we re-shored some of the processing and added value before exporting?

Downstream is usually where the big margins are – analysis by CRU Group suggests downstream lithium battery production could be worth $30 billion.

But while Australia is the world's largest lithium producer, it only captures a tiny fraction of the ultimate value of the mineral it exports – as little as 0.5%.

However, the lithium may end up coming back into Australia, once the value has been added. In fact, the ABC reports that three-quarters of the lithium used in Tesla batteries globally comes from Australia.

The question is, how can Australia become an advanced manufacturer of critical minerals products and capture the value that other countries are currently reaping?

It should be simple. As well as having land full of natural resources, Australia also has people with the intelligence and skills to transform these raw materials into higher value items, like batteries.

Let’s take a look at what’s being done in 2023:

In October, the Federal Government announced that the National Reconstruction Fund will include the $1 billion Value Adding in Resources Fund to work alongside the $2b Critical Minerals Facility.

The idea is to help drive growth in the critical minerals sector, including rare earths.

Queensland Pacific Metals (ASX: QPM) is ensuring the sustainable production of a number of battery metals.

The company is developing the 100% owned Townsville Energy Chemicals Hub (TECH) Project, a modern and sustainable battery metals refinery also located near Townsville.

Through this project, the company is aiming to become a leading supplier of high-grade advanced nickel – a primary component of lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles.

Credit - Australian Govt 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy Report March 2022

In a promising move by the government, Australia’s first National Battery Strategy was launched in February this year. This strategy is designed to complement Australia’s new Critical Minerals Strategy to articulate “a clear pathway for integrated, end-to-end onshore battery minerals supply chains” and “ensure Australia maximises its economic potential in these fast growing and lucrative markets”.

In short, the strategy is designed to find ways to get Australia manufacturing batteries.

Part of this plan is to create a Battery Manufacturing Precinct in partnership with the Queensland State Government, and to support 10,000 New Energy apprenticeships.

The government states that the value of batteries will likely rise 10-fold in the coming decade.

There are already Australian manufacturers growing their capabilities in this crucial industry – one of them is Energy Renaissance (ER), an Australian lithium-ion battery technology and manufacturing company based in Tomago in the New South Wales Hunter Valley.

The manufacturer says it is “committed to creating and making all-Australianlithium-ion batteries from cells to complete battery solutions and accelerating Australia’s transition to a clean energy superpower”.

Another Australian-based company, VSPC, has developed processes for the cost-effective manufacture of high-purity, nano-scale materials for the lithium-ion battery market. With a goal to improve current Li-ion production processes, the company designs, creates and supplies materials in its electro-chemistry laboratory and pilot production facility in Brisbane.

Global demand for vanadium in batteries is predicted to outpace supply before the end of the decade. But Queensland can help – the state has about 30% of the world’s vanadium resources with world-class deposits located in accessible marine shale.

That’s why an Australian-first critical minerals demonstration facility is going to be built in Townsville in northern Queensland. The $75million facility, which will start operations in 2025, will process critical and rare-earth metals needed for the clean energy transition, including vanadium.

As the Premier said, “Vanadium has the potential to be the Eureka moment for North Queensland.”

The facility is part of a $150m commitment announced in Queensland’s 2022-23 State Budget Update in December. The Premier predicts the market will see the quality of Queensland’s valuable resources and have the confidence to invest in commercial scale facilities and downstream manufacturing infrastructure.

Australian Vanadium Limited (ASX:AVL), an emerging producer of vanadium in Western Australia, is eyeing downstream opportunities in the vanadium market – specifically, vanadium electrolyte manufacturing and opportunities for vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFB).

Through its battery supply subsidiary, VSUN Energy, AVL is working to create the end market for VRFBs at home in WA.

While lithium-ion batteries remain the dominant technology in energy storage, larger scale vanadium flow installations are constantly being rolled out. VRFBs are considered to be safer (they don’t catch fire) and longer lasting than their lithium counterparts with a lifespan of 20-plus years. The company plans to use its own vanadium powder for its flow batteries.

The company is also working to develop a smaller residential VRFB for those looking for an alternative to lithium-ion batteries.

Historically Australia has focused on exporting raw materials, but a very big opportunity could be missed by not moving further downstream and transforming the critical minerals into complex items for both local and international markets. There’s no doubt we’re moving in the right direction, but with other countries already using our resources to manufacture batteries on a large scale, have we already fallen too far behind? Only time will tell.